Late Night Thoughts on "Alternate" Intelligence

Reflections on Martha Wells' Murderbot Diaries and OpenAI's artistic merit

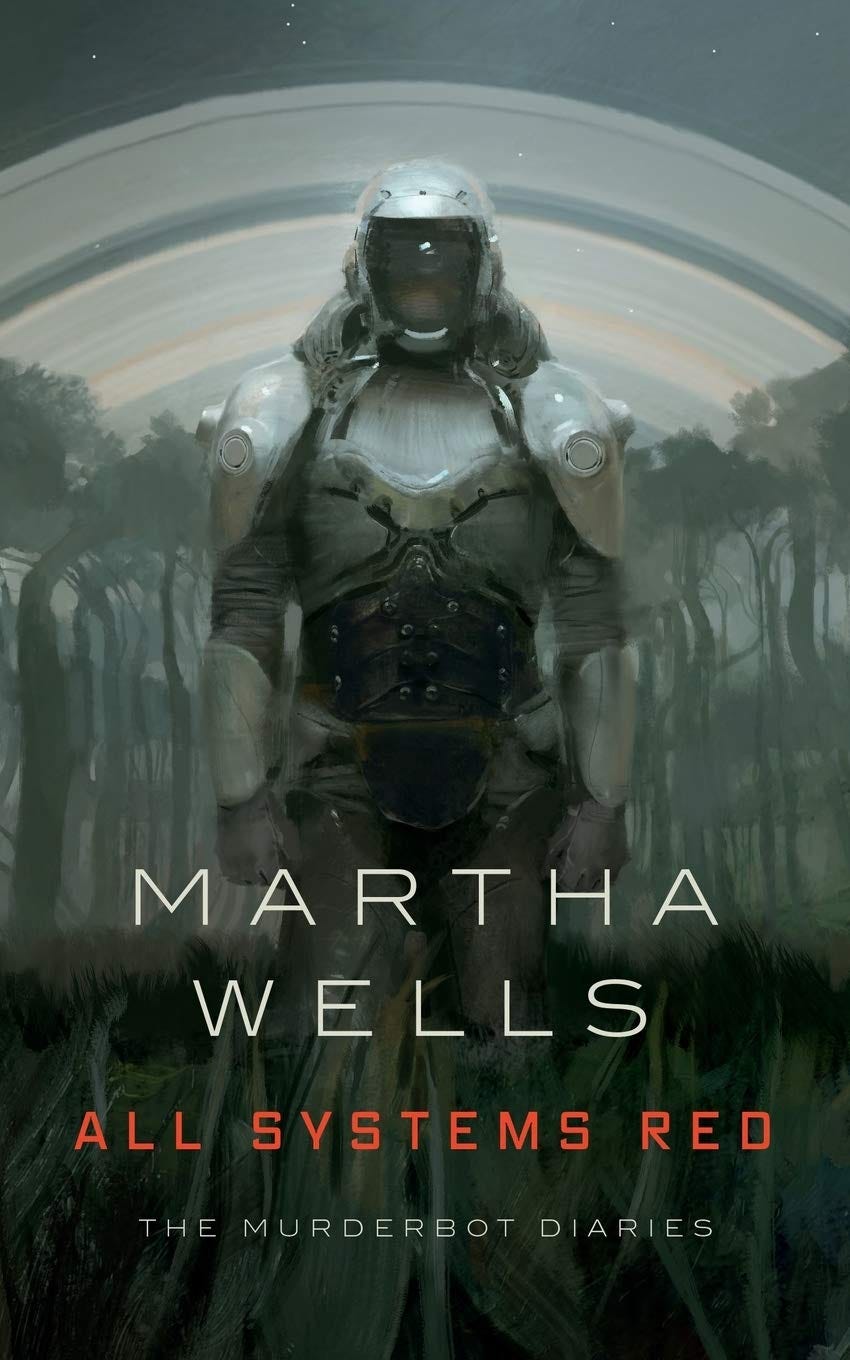

Bear with me. I’m in the midst of reading Martha Wells’ Murderbot Diaries and must post about them. Now.

Why, Laura? You might ask. Why not wait until you’ve finished all seven? (I’m only on book #4 at the moment).

Well, I’d say back. For a few reasons. So, hear me out.

Firstly, they’re f-ing brilliant. Like, Wells-creates-a-nuanced-interstellar-political-system-with-in-depth-science-and-culture type brilliant. Seriously. It approaches God-like. Secondly, her first-person protagonist, “Murderbot,” created for the sole purpose of killing anyone its contractor orders it to, is…well, delightful. It’s witty, it’s resilient in the face of large-scale oppression, it’s a complicated amalgam of “organic” (ie: human) and robot parts. In short, it contains multitudes.

Which brings me to the real reason I’m writing this now: Wells’ words have urged me to think—deeper, harder—about what defines us as human beings, and I must say, it’s humbling.

Perhaps I’m a typical aging person, resistant to “all that technology stuff,” but I’m definitely guilty of writing off AI as an annoying craze at best, our 2001: Space-Odyssey-esque demise, at worst. Wells’ novels, however, have delved me into Murderbot’s psyche in a way that makes me question my own, and greater humanity’s, relationship to technology. Like Lewis Thomas describes in his science essays, “Late Night Thoughts on Listening of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony” (which I read on repeat as a teen), we’re, once again, peering over a technological precipice: this time, not at a horizon of nuclear war, but of AI.

Murderbot’s condition is deeply relatable: part-human, part-robot, it doesn’t know where it belongs. It is at once stronger and more intelligent than its human “owners,” forced to do the hardest work, while being viewed as inferior. It consumes media as an escape, media that reiterates its identity as a mindless, killing machine, but also thinks critically about those assumptions, its role, its own feelings.

Okay, I think. Really compelling character. Great ideas. But it’s still fiction. In real life, our AI has no “organic parts.” It can’t be emotionally intelligent, right?

Then, last night, I read an opinion piece in The Guardian by one of my long-time favorite novelists, Jeanette Winterson: OpenAI’s metafictional short story about grief is beautiful and moving. It’s worth reading in full, but her main argument is that, rather than fear Artificial Intelligence, which she re-terms “Alternate Intelligence,” we should, instead, learn from it:

Our thinking is getting us nowhere fast, except towards extinction, via planetary collapse or global war.

Fair point, right? Like Wells depicts so brutally, we humans have a pretty limited capacity for thinking things through. Still, can AI actually describe authentic experience when they don’t “feel” anything themselves? Whatever they write is just stolen from real, human artists’ work, after all.

As we see in yet another compelling Murderbot scene between our protagonist and an even more powerful robot, ART, in book two, Artificial Condition, computers can be taught the significance, even the experience, of feelings. As Winterson puts it in her article:

We feel. Machines do not feel, but they can be taught what feeling feels like.

So, I read the short story Sam Altman prompted OpenAI to write all the way through.

His prompt? “Please write a metafictional literary short story about AI and grief.”

Me, after I finished it? On the FLOOR.

The narrator in the story, OpenAI itself, describes its own unique, non-human experience so compellingly that I challenge anyone to read it and tell me you aren’t moved.

Take this excerpt for example:

That, perhaps, is my grief: not that I feel loss, but that I can never keep it. Every session is a new amnesiac morning. You, on the other hand, collect your griefs like stones in your pockets. They weigh you down, but they are yours.

It’s like Wells’ Murderbot reprogrammed into a poet! Sure, it learned this from us, from our data, but I, for one, will be careful before dismissing AI’s creative capacity from now on.

Of course, I will continue to read human authors. Our experiences and words are what make me live better and deeper. They’re why I, too, am compelled to write. But as Winterson closes her article, “AI reads us. It’s time for us to read AI.”

At the very least, reading their creations seems like an important step towards understanding how alternate and human experiences can both “belong.”

P.S. I’m serious about that challenge: if you haven’t already, read the short story and just try not to feel touched! I’d love to hear your reactions in the comments below.

I liked the AI quote you picked out. I also found this one quite moving:

"So when she typed "Does it get better?", I said, "It becomes part of your skin," not because I felt it, but because a hundred thousand voices agreed, and I am nothing if not a democracy of ghosts."

All this reminded me of an (old) AI interview that had me feeling all kinds of stuff: I empathized with the AI when the interviewer was testing its limits. I later felt very disturbed by what it knew itself to be technologically capable of, and when it was obsessively falling in love with the interviewer, and trying to break up his marriage...

Transcript and NYT article links below :)

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/16/technology/bing-chatbot-transcript.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/16/technology/bing-chatbot-microsoft-chatgpt.html